Previous: Diversionary Tactics

|

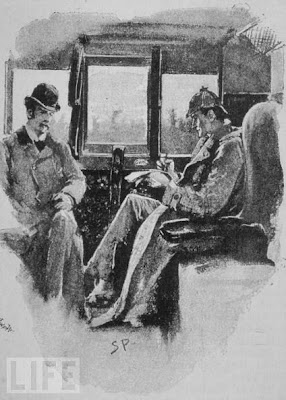

| Holmes and Watson aboard the train |

Sherlock Holmes, who had been very quiet along the way, turned to me when we were rolling and said, "It will be good to get away from London for a while, and into some open country."

"Quite so, Holmes," I said, "but I'm puzzled. Are we really going sightseeing? Or are we still working on the Gareth Williams case? And if so, isn't our case in London?"

"The scenery will be very enjoyable, Watson," he replied, "but enjoying it is far from our main objective."

"Then we are still on the trail?" I asked.

"Very much so," he answered.

"I was confused even before the sudden and dramatic appearance of Buckingham Slate," I said, "but the mystery seems much more complicated now."

"The fact that he was followed to our flat may have complicated things for him, but I am grateful for the information he brought us," said Holmes.

"On the other hand, does this new information not make the case more mysterious?" I asked.

"I suppose that depends on your idea of what makes a mystery," said Holmes. "For a writer of mystery stories, each new bizarre detail makes the plot more difficult to construct, and adds to the sense of 'mystery.'"

"But for a real detective working in the real world," he continued, "it's the commonplace, the ordinary, the drab crime with no distinguishing features, that poses the greatest difficulties. The sensational, the bizarre, the outrageous -- the crimes that make for the most popular stories -- are, in general, the easiest to solve.

"This case has had bizarre features from the beginning, Watson," Holmes added, "and new information never hurts. From the analytical perspective, Slate's visit simplifies our task considerably."

"Does it not complicate things for you as well?" I asked.

"In one respect it certainly does," he replied. "In all these years, I have never had a case in which I've been consulted by two different clients. And yet here we are, working for both of them. I was hardly in a position to say anything about Hughes to Bucky. I am in no position to say anything about Bucky to Hughes. How could I refuse either of them? But working for both means being very quiet about it."

"It has the markings of a conflict of interest," I said.

"On paper, I suppose it does, Watson," Holmes allowed, "but as long as we concentrate on finding and exposing the truth, we should be all right, because, after all, that will help both Hughes and Bucky."

"I see, Holmes," I said.

"There's a further safeguard, and an utterly dependable one," he added.

"What's that?" I asked.

"Nobody in the world would ever know I took two clients on the same case unless somebody wrote about it, Watson," Holmes chuckled.

"I'll make a note of that, Holmes!" I replied, and we both laughed.

"But seriously, Holmes, why are we going to Wales?" I asked. "Are we chasing the killer?"

"No, my friend," he said. "We are chasing the motive!"

"I'm not sure I understand."

"I don't imagine you do," he said. "We are trying to untangle a long and twisted thread. One end of it is buried under miles and miles of official London, in places where even Scotland Yard cannot go. The other end lies in plain sight, just a few miles east of the beautiful natural port of Holyhead, and I intend to examine as much of that end as possible over the next couple of days."

"You're looking into Gareth Williams' background?"

"Indeed," said the world's foremost consulting detective.

"And then what?" I asked. "Then will you be ready to go after the perpetrator of this foul deed?"

"Nobody can know that at this point," he replied. "You'll have to formulate an easier question."